Oceanographer, Povl Abrahamsen, has returned to the Amundsen Sea in west Antarctica on the Korean research ship, Araon. One of his tasks is to assist with the deployment of ten autonomous phase-sensitive radio echo sounders (ApRES) on ice shelves in the region. These downward-looking radars are dug into the snow at the surface, and measure tiny changes in the ice thickness down to the sea hundreds of metres below. Read his blog here:

For almost all of this trip so far the weather has been pretty dreary: grey skies, snow showers, and poor visibility. But when we reached the western edge of Getz Ice Shelf, the first of our deployment areas, everything seemed to be clearing up – but with quite a few clouds on the horizon. We loaded up “our” helicopter with shovels, tools, a few instruments, survival equipment in case we weren’t able to return to the ship for a few days, and four people in addition to the pilot: three scientists (from the Korea Polar Research Institute, the University of Gothenburg, and BAS, respectively) and a field assistant (an experienced Korean mountaineer).

And then we set off for our first site at 7 pm in the evening. After we lifted off the ship we made straight for the ice shelf, and then continued inland about 500 feet off the surface: the sites are about 70 km inland.

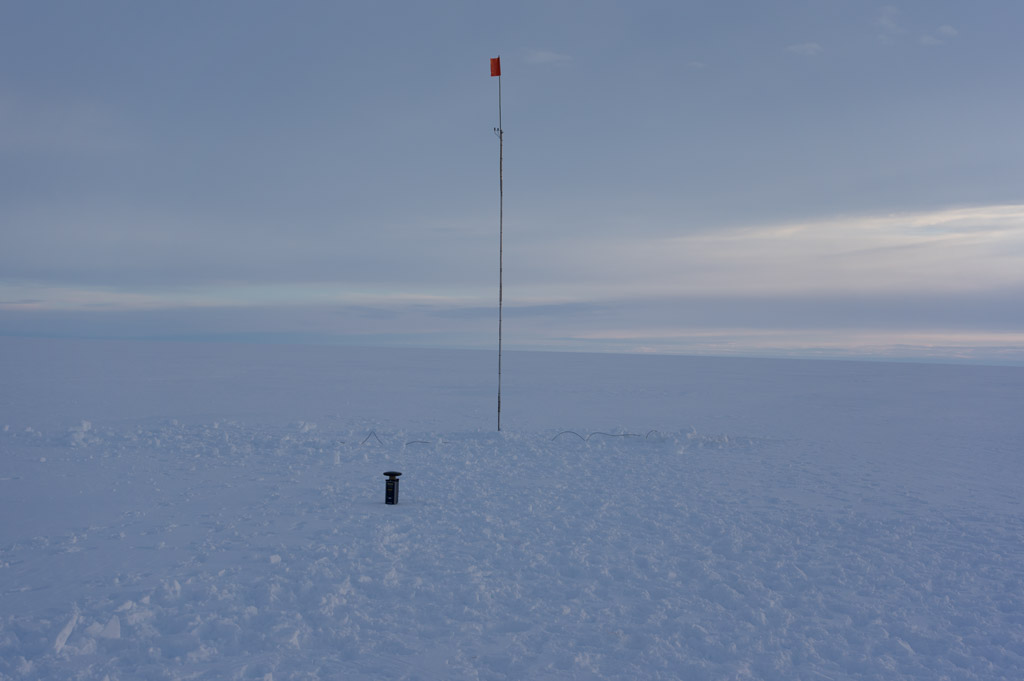

The weather was still a bit dull, making it difficult to make out the surface, and the pilot considered turning around. But then we reached a gap in the clouds, and everything became nice and clear. The pilot decided to continue to the first site, and we landed softly on the snow. With the rotor blades still spinning, our field assistant stepped out onto the ice first, and checked the area around the helicopter for crevasses. Once he gave the pilot the thumbs up, the helicopter was shut down, and three of us started unloading and digging the holes for the radar, while the fourth person started preparing some other survey equipment. Although the snow was quite well packed, it wasn’t too bad digging down: we needed two shallow holes for our two antennas (one to transmit, another to receive), and a deeper hole for the radar itself and a large battery to power it. After a bit of time on the ground to assess what the weather was doing, the pilot flew back to the ship to bring us the main radar equipment. And once he had returned, we were finally able to assemble the antennas, plant them in the ground, raise a 6-metre mast with GPS and satellite antennae, and an orange flag on top, and finally turn on the radar for some tests. We were relieved when we got a nice clear return from the base of the ice 480 metres below us.

At this stage, the sky was brightening up: we are on New Zealand time, but are quite a lot further east, so local midnight is 9 pm on our clocks.

After packing up our equipment and depoting most of it on the ice, we boarded the helicopter and set off for the next site. Luckily weather seemed to be improving, so the pilot was happy to drop us off and return for the remaining equipment from the first site. From there on, we continued until we had finished four sites, and returned to the ship rather tired in the early hours of the morning, just over ten hours after we had left.

The radars will remain in Antarctica for the next two years, measuring the thickness of the ice beneath them every two hours. While they do send back some of their data by satellite, the full datasets are stored inside the instruments, so someone will need to return and dig them up: an unenviable job, as they may be covered by five more metres of snow by then. In the meantime, we are back on the ship, catching up on sleep, resuming our other work, and looking forward to deploying the next six instruments